|

Home

Twin

Cam Tech Tip Download

Tech Tip Articles

Fun to Ride Guide

Custom Engine Estimate

Custom Engine Building

Other

Products and Services

Perry's Bio

Friends

Catalog Request

Order

Links

| |

|

PAGE

1: FROM SOAPBOX DERBY TO THE NHRA CHAMPIONSHIP |

|

Even as

a little kid I had a natural instinct to build things with wheels and

make them go fast.

I

was born in Ohio and raised in Florida, where I built and raced soapbox

speedsters like the one to the left. |

|

In 1957 I bought my first

motorcycle. It was a ’52 Indian Warrior, a 500 c.c. vertical twin

with, shall we say, modest power. Even back then I was feeling the

“need for speed” and wanted my bike to be the fastest at school.

I

was studying auto mechanics then, and got myself transferred to machine

shop so I could go beyond sticking on parts and get right into the heart

of the motor, where performance tuning really comes from.

With

my developing skills in metal fabrication, I could make my Indian

unique. My first task was to port the heads for better airflow. Then I

added a bigger carburetor, valves and pistons. After some trial and

error, I achieved my goal: the fastest bike at North Miami High School.

More important, I knew at a very early age what I wanted to do with my

life.

|

Perry's first bike,

a 1952 Indian Warrior |

Harvey Crane,

"The Master"

|

Learning from the Master

In

1961 I went to work for Harvey Crane, whose name was a legend in racing

even back then. I was the fifth man in his small machine shop in

Hallandale, Florida — a lowly apprentice but aware of my extreme good

fortune in having the opportunity to learn directly from “the

Master.” I started out porting Chevrolet heads for competition. After

a few months my duties were expanded to valves, seats and final

assembly.

We

made those old Chevy valves very thin, with seat widths measuring only

.030 for intake and .045 for exhaust. I ground the height, width, and

cut the seat pockets by hand with a 70-degree cutter. My only guide for

this precision work was a hand-held mechanical pointed divider that I

adjusted by eye and feel. In that shop I developed the “tuner’s

instinct” for working with metal that has served me well for 30 years.

|

|

After

a little while Harvey trusted me to do all the heads for the dragsters

he sponsored. All were top-performance “rail” jobs. This was where I

learned the techniques for getting maximum power out of two-valve heads,

while maintaining reliability and—all-important in race

engines—managing heat buildup.

Building the motor that beat Don Garlits

Then

came the time with Pete Robinson from Atlanta. He was a drag racer who

had been using Harvey’s cams for years. This was my opportunity to

build heads for a world-class competitor in racing’s most extreme

engine tuning environment: Top Fuel.

Pete

was an advocate of titanium, and made a lot of parts out of this exotic

and hard-to-work-with metal for his Top Fuel dragster so it would be

lighter and stronger at the same time. (I should also mention that I

tested and matched all his valve springs myself because he was turning

this motor over at 10,000 rpm.)

In

our second year of collaboration, Pete beat Don Garlits for the world

Top Fuel championship. Pete held onto that trophy for three years, when

tragedy struck and he was killed in a crash.

After

five years in the high-stress world of drag racing, I was burned out and

ready for a change. I wanted to get back to my first love, motorcycles.

At that time the hotbed of American motorcycling was California.

|

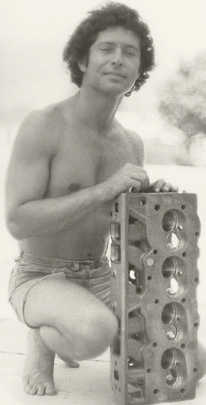

Perry with an early

project: a Chevy head from a drag racing "rail job".

The car to beat: a

rare photo of "Big Daddy" Don Garlits' 1963 dragster.

|

|

CLICK ON PAGE 2:

L. A. DURING MOTORCYCLING'S GOLDEN AGE

|

|